Chess - Inspired Strategies for Effective Teaching Practices

A bishop slips across the board, almost unnoticed.

A pawn suddenly shifts the balance of the game.

Within moments, a planned strategy unravels.

You lean back, reconsider your next move.

This is not just chess; it is a lecture hall on a Monday morning.

You walk into class with polished slides and a bulletproof teaching plan in your mind. But within minutes, you sense something is off. Students are not responding. Their eyes flicker with confusion. It is not philosophy or literature. It is last week’s grammar. Just like in chess, the unexpected forces a new strategy.

“Without the element of enjoyment, it is not worth trying to excel at anything,” said Magnus Carlsen, the world’s top chess grandmaster. Although reflected in the context of chess, this insight resonates deeply with the teaching profession, where excellence depends not only on expertise but also on thoughtful strategy, mental resilience, and a clear objective.

Much like the game of chess, teaching involves anticipating challenges, responding flexibly to change, and making deliberate decisions in real time. While chess may appear too quiet and complicated to some, it is, at its core, a dynamic test of focus and foresight, qualities that parallel effective teaching practices in higher education. This article explores how the principles embedded in chess, such as strategic planning, adaptive thinking, emotional regulation as well as reflective growth, serve as powerful tools to support more impactful teaching.

Strategic Planning for Effective Classroom Instruction

First and foremost, effective teaching begins with strategic planning. As educators, it is essential to prepare lessons and classroom activities well in advance, considering several steps ahead of actual delivery. In chess, success is elusive for those who fail to plan, whereas a well-planned strategy keeps the game intact and increases the chances of achieving victory. Similarly, strategic lesson planning ensures that the teaching and learning process remains focused and purposeful from start to finish.

In the field of language education, strategic planning as discussed by Aubrey and Philpott (2022) refers to the intended preparation undertaken before a communicative task, aiming to improve learners’ fluency, complexity, and accuracy. Although their study focuses on learners, the same principle can be applied to the context of teaching. Teachers who engage in strategic planning are not merely organising content, but are also mapping out a sequence of instructional steps that align with clear learning goals. This includes identifying key skills, selecting suitable materials, considering students’ difficulties, and ensuring lesson progression. Effective instruction, therefore, is not spontaneous. It is the result of intentional decisions made well in advance to support meaningful learning experiences.

This concept resonates with the strategic thinking employed by chess players. According to Sgercia and Castellanos (2024), effective chess strategies involve assessing positions, setting long-term goals, and making calculated moves such as controlling the centre of the board, developing pieces efficiently, castling for king safety, and understanding pawn structures. While strategies focus on overarching plans, tactics involve short-term manoeuvres to respond to immediate threats. Likewise, classroom planning involves both long-term vision and day-to-day flexibility. Teachers must construct coherent lesson sequences while remaining responsive to classroom dynamics, unexpected challenges, and real-time student needs. Just as a chess player adapts to the opponent’s move without losing sight of the endgame, a teacher must adjust instructional delivery while staying aligned with the intended learning outcomes.

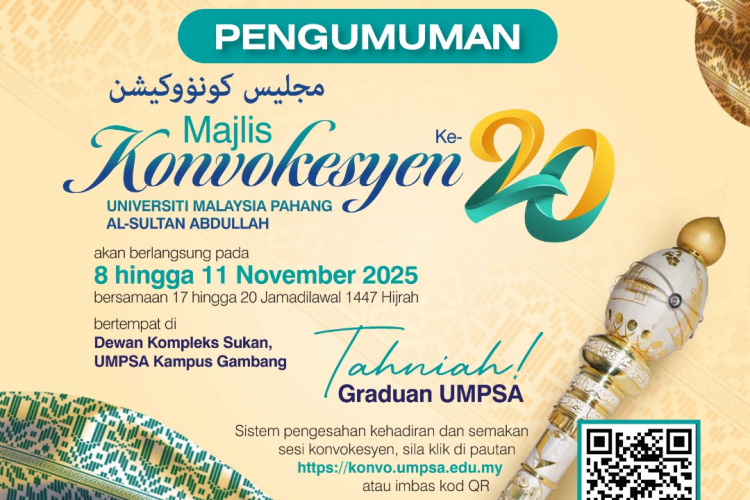

At the Centre for Modern Languages, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (UMPSA), for instance, strategic planning is evident in the way language classes are designed and conducted. Given contact hours of four to six hours per week for each section taught, every language lesson must be purposeful and well-structured. Lessons typically begin with induction activities such as thought-provoking questions, vocabulary prompts, or brief interactive tasks that activate prior knowledge and engage students from the outset. This is followed by a clear presentation of lesson outcomes, which serve as tangible learning targets for the session. Instruction is delivered through interactive methods that encourage participation, such as group discussions, pair work, project-based tasks, and student presentations. Towards the end of the lesson, students are encouraged to reflect on what they have learned through self-assessment, feedback sessions, or brief written reflections. These stages of instruction are carefully planned to ensure that each class session contributes to the overall development of learners’ language competence and confidence.

Adaptive Instruction in Responding to the Unpredictable

Chess is a game where every move invites reassessment. No two matches unfold the same way, as each decision from an opponent shifts the dynamics, requiring creative adjustments. Teaching operates in much the same manner. A lesson may begin with clear objectives, but the real-time responses of students, which include confusion, disengagement, or unexpected questions, often demand a shift in strategy. In both fields, adaptability becomes a core survival skill.

This ability to pivot is known as adaptive instruction. It involves adjusting one’s teaching approach based on students’ needs, energy levels, or unforeseen challenges. For instance, if students struggle with a concept, the teacher may switch to a visual explanation or restructure the activity entirely. These immediate decisions mirror how chess players revise tactics mid-game. Reyes-Millán et al. (2024) show that adaptive strategies can improve learning outcomes by helping educators respond more effectively to real-time classroom dynamics.

Adaptability in teaching is not about abandoning structure; it is about reading the room, responding with intention, and staying resilient when things veer off-script. Just as every move in chess is a chance to rethink and recover, every classroom moment is an opportunity to refine practice. The ability to embrace unpredictability, rather than resist it, is what transforms a good teacher into a reflective, responsive educator.

Composure and Mental Discipline in Teaching

Imagine this. Shakirah, a language teacher, is midway through explaining a complex grammar structure when the lecture hall’s projector suddenly shuts down. Her slides disappear from the screen, and confusion begins to spread across students’ faces. Rather than reacting with worries, she calmly picks up a whiteboard marker and continues the lesson manually. To her surprise, the students became more engaged than before.

This calm response mirrors the mindset developed through chess, particularly in high-pressure formats like speed chess. In such games, players must manage time constraints, react to the moves, and make decisions immediately. All without losing focus. Also, educators must navigate classroom disruptions and student behavior while maintaining composure. The ability to think on one’s feet, stay emotionally grounded, to shift strategies in real time is critical in both fields.

Chess reinforces the importance of recovering quickly from mistakes. A poor move cannot be undone, but it can be followed by a stronger one. The same applies to teaching. Group activities may fall flat, and students may struggle with lessons. Effective educators, like chess players, continue forward. Seeley et al. (2024) highlight, emotional regulation and rapid decision-making skills nurtured in structured, problem-solving environments like chess are essential for maintaining performance under pressure. These qualities not only support instructional resilience but also create an atmosphere where students feel secure to learn and try again.

Reflective Growth

Adam, a colleague who teaches English, once designed a lesson on sentence patterns that he believed would be interesting. However, by the end of the session, he sensed that something had gone wrong. The students appeared more puzzled. He had introduced multiple grammar rules simultaneously, hoping the students would connect the dots. That evening, Adam replayed the lesson in his mind, like a chess player reviewing a lost game. He asked himself, “Where did I go wrong?”.

This kind of reflection mirrors the analytical process chess players undertake when evaluating their moves. Educators engage in similar thinking. Professional growth in teaching is not solely achieved through experience but through reflection. In Adam’s case, he revised his approach for the next class by simplifying explanations and incorporating clearer examples. The results were great. His students understood the material clearly.

Reflective practice is not only about correcting errors but about refining one’s craft. Just as chess players improve by studying their games, educators examine their lessons. They ask themselves questions such as “What worked well?” and “What did not?”. Reflection can take many forms, such as a quick note in a teaching journal or a conversation with a colleague. These moments of self-assessment sharpen a teacher’s judgment and enhance continual professional development.

The analogy between chess and teaching reveals profound insights into the nature of effective educational practice. Both disciplines demand planning, adaptive execution, emotional regulation, and continual reflection. Just as a skilled chess player anticipates multiple outcomes, educators craft flexible strategies that respond to the changing rhythms of the classroom.

Teaching is like chess: a quiet pursuit of mastery, built on strategy, patience, and reflection. Each lesson taught and each student inspired transforms the teacher, deepening both skill and wisdom.

The next day,

A new game begins.

Not always a checkmate,

But always a move forward.

References:

Aubrey, S., & Philpott, A. (2022). Use of the L1 and L2 in Strategic Planning and Rehearsal for Task Performances in an Online Classroom. Language Teaching Research, 29(3), 1139-1164. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221077421

Reyes-Millán, M., Vázquez-Villegas, P., & Membrillo-Hernández, J. (2024). Using an Adaptive Learning Tool to Improve Student Performance and Satisfaction in Online and Face-to-Face Education for a More Personalised Approach. Smart Learning Environments, 1(6), 1-24.

Seeley, L. N., Packard, D., & Regehr, C. (2024). Enhancing Emotional Regulation and Decision-Making in High-Stress Professions: A Review of Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(2), 134–148.

Sgircea, R., & Castellanos, R. (2024). Chess Strategy: Complete Guide. The Chess World. Retrieved from: https://thechessworld.com/articles/general-information/chess-strategy-c…;

By: Nur Anisnabila Dianah

E-mail: nuranisnabila@umpsa.edu.my

Language Teacher

Centre for Modern Languages

Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (UMPSA)

By: Hanisah Bon@Kasbon

E-mail: hanisah@umpsa.edu.my

Senior Language Teacher

Centre for Modern Languages

Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (UMPSA)

By: Leong Hui Theng

E-mail: leonghuitheng@umpsa.edu.my

Language Teacher

Centre for Modern Languages

Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (UMPSA)

By: Nor Safura Nordin

Consultant Fellow

Centre for Modern Languages

Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (UMPSA)

- 202 views