Why Malaysia’s ‘Ir.’ is Stagnating?

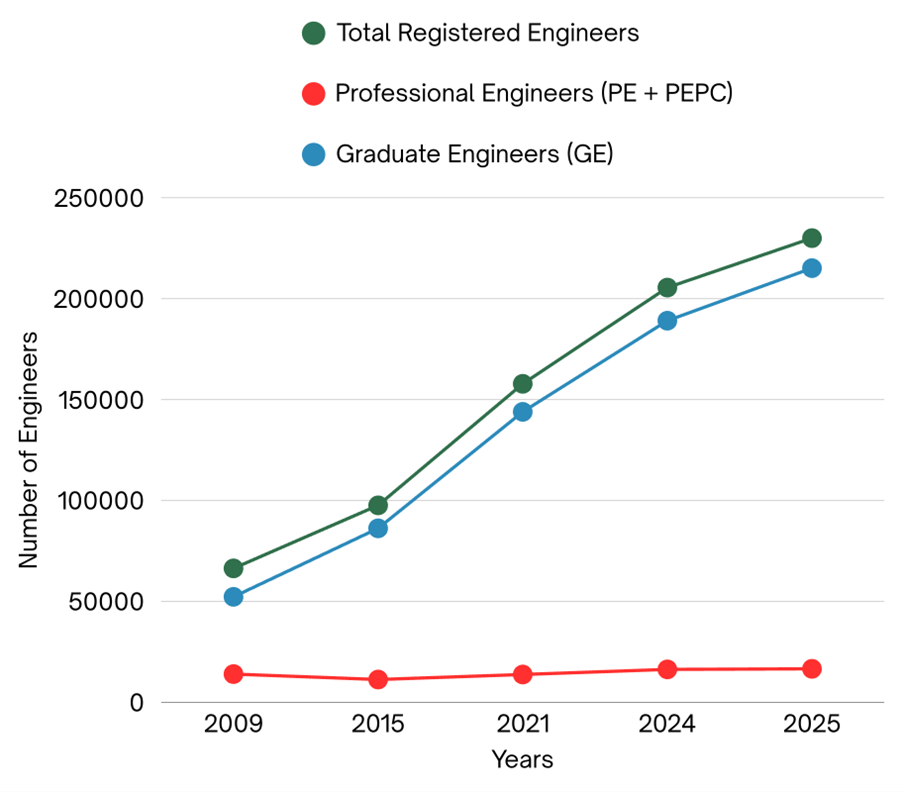

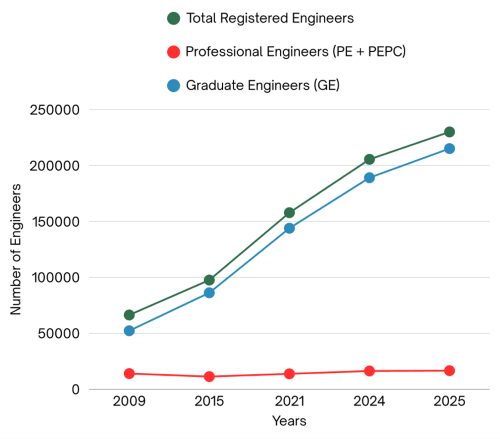

At first glance, the Board of Engineers Malaysia (BEM) appears to be a resounding success. Between 2009 and 2024, the number of engineers on its books more than tripled, soaring from approximately 66,000 to over 205,000. Yet, this impressive growth masks a critical weakness: the number of Professional Engineers (PEs), those with the coveted ‘Ir.’ title who are authorised to sign off on projects, has failed to keep pace, creating a bottleneck that could stifle national development.

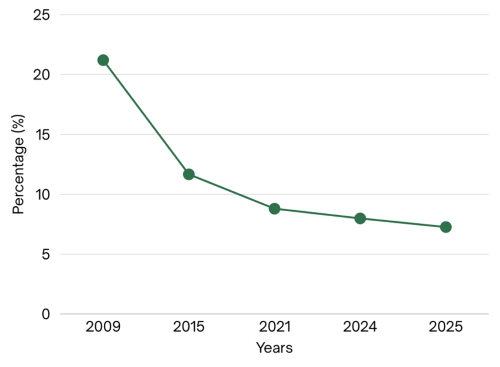

Data culled from official reports and presentations reveal a widening gap. In 2009, BEM’s register contained 14,084 PEs and 52,350 graduate engineers (GEs). This meant roughly one in four registered engineers had completed the rigorous experience and examination requirements needed to use the ‘Ir.’ prefix. They were the seasoned professionals legally empowered to take ultimate responsibility for engineering works.

However, by 2015, the landscape had shifted dramatically. While the total number of registered engineers swelled to nearly 98,000, the count of PEs fell to 11,387. The ranks of GEs, by contrast, had ballooned to 86,259. This influx of graduates, combined with a decline in licensed professionals, shrank the proportion of PEs to just 12%. The pipeline from university to professional practice was beginning to look less like a highway and more like a congested lane.

The trend has only accelerated. A BEM presentation in March 2021 reported 157,835 registered engineers. Within this group, a mere 13,878 were professional engineers (split between 9,056 with a Practising Certificate and 4,822 without), while a staggering 143,957 were GEs. By this point, fewer than one in ten registrants were fully licensed. Fast forward to January 2024, and columnist Hong Wai Onn noted the registry had grown to 205,500, with the proportion of PEs hovering at a meagre 8%, or around 16,400 individuals.

The latest statistics from the BEM official website, as of 31 July 2025, paint an even starker picture. The number of Graduate Engineers has climbed to 219,268, supported by 18,223 Engineering Technologists and 6,403 Inspectors of Works. In contrast, the combined number of Professional Engineers and Professional Engineers with Practising Certificates stands at just 18,130. Within a total registered body of over 262,000, this means the proportion of fully licensed engineers remains stagnant at a mere 7%, highlighting the persistent challenge of converting graduates into professional leaders.

Why is the Pipeline Blocked?

Several factors explain why so few graduates complete the journey to professional status. The pathway itself is demanding, requiring a minimum of three years of supervised practical experience before sitting for the Professional Assessment Examination (PAE). Compounding this, a surprising number of graduates and their employers seem unaware that registration with BEM is a legal prerequisite to practise as an engineer in Malaysia. As Hong Wai Onn observed, “There appears to be a lack of awareness among both employers and students,” leading to many graduates performing engineering roles without the necessary legal standing.

Economic incentives also play a significant part. Malaysian engineers who find lucrative work overseas often bypass BEM registration altogether. For those who remain, the immediate financial and career benefits of pursuing professional status may not be obvious, particularly if their employers do not require it. This scenario creates a cycle of complacency that undermines the profession’s integrity.

What is at Stake for Malaysia?

This chronic shortage of professional engineers is not merely a statistical curiosity; it has profound implications for the nation. PEs are essential for ensuring public safety and accountability. Only they can legally approve structural drawings, oversee critical construction phases, and assume legal liability for engineering decisions. Without a sufficient number of them, Malaysia faces the risk of delays in major infrastructure projects and an increasing dependence on foreign expertise to fill the gap.

The deficit also reverberates through the academic world. The Engineering Accreditation Council (EAC) requires that a significant portion of teaching staff in accredited engineering programmes are registered professional engineers. With a limited pool of ‘Ir.’ holders to draw from, universities find it increasingly challenging to meet this standard, potentially affecting the quality of engineering education for future generations.

Charting a Path Forward

To bridge this divide, experts advocate for a multi-pronged approach. Targeted awareness campaigns are needed to remind employers and graduates that practising as an engineer without BEM registration is illegal. Universities could also play a more active role by tracking their graduates’ registration rates and investigating the barriers they face.

There are, encouragingly, signs of progress. BEM has modernised its registration system and is collaborating with the Institution of Engineers Malaysia (IEM) to streamline the professional assessment process. As shown in Figure 1, the number of PEs has finally started to climb, from 13,878 in 2021 to 18,130 today. However, this modest increase is dwarfed by the relentless surge in graduate registrations, causing the overall percentage of PEs to continue its decline to just over 7% (Figure 2).

Ultimately, Malaysia has proven it can produce engineering graduates in vast numbers. The challenge now is to convert them into fully-fledged professionals. As I have often remarked, “It’s not just about how many engineers we have; it’s about how many can actually take responsibility for engineering work.” Until that bottleneck is cleared, the ‘Ir.’ title will remain a rare badge of honour rather than the standard for a thriving profession.

By: Professor Ts. Ir. Dr. Wan Sharuzi Wan Harun

E-mail: sharuzi@umpsa.edu.my

Writer is a Principal Research Fellow, Automotive Engineering Centre, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (IMPSA).

- 649 views