Nanotechnology: The Next Big Leap Beyond Miniaturisation

For decades, the electronics industry has advanced by making devices smaller and more powerful. From laptops to smartphones and wearable gadgets, this progress has relied on shrinking transistors, the tiny switches that control electrical signals, while increasing processing speed. Traditional transistors work by controlling the flow of electrical current, but as their size approaches just a few nanometers, quantum effects such as electron leakage and heat dissipation make this approach less efficient. To overcome these challenges, researchers are exploring new transistor designs that harness quantum phenomena like tunneling and spin-based logic, enabling faster switching and dramatically lower power consumption.

“There’s plenty of room at the bottom’’ – Richard Feynman

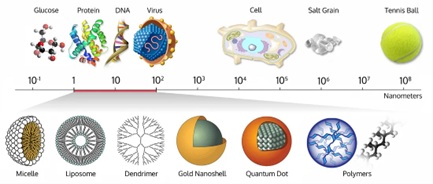

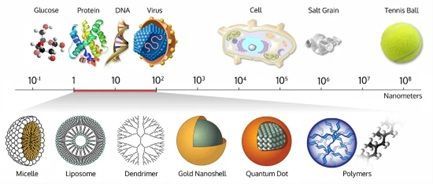

The concept of working at the atomic scale was introduced by physicist Richard Feynman in 1959, who famously declared, “There’s plenty of room at the bottom.” His vision of manipulating individual atoms and molecules has evolved into nanotechnology, a powerful toolkit that now goes far beyond miniaturisation. While early progress focused on shrinking components in all dimensions, Moore’s Law, which predicted the doubling of transistor density every two years, is reaching its physical limits. This has led to a new direction: creating ultrathin nanostructures that are only a few nanometers thick but span centimeters laterally, achieving extreme aspect ratios that defy conventional engineering. At these scales, gravity and traditional mechanical constraints lose significance, opening the door to structures with unique mechanical, optical, and quantum properties. These innovations are enabling breakthroughs such as mirrors for interstellar lightsails, ultrasensitive force sensors, and scalable quantum hardware, which could redefine computing, space exploration, and precision measurement.

Nanotechnology is driving advances in electronics through nanowires and molecular-scale devices. Nanowires, with diameters ranging from just 10 to 100 nanometers and lengths exceeding 100 micrometers, exhibit remarkable electrical properties and scalability, making them ideal for developing transistors, sensors, and logic gates that operate with significantly lower power consumption. Molecular electronics pushes the boundaries even further by designing circuits at the level of individual molecules, requiring precise control of electron transport and molecular interactions. Another emerging concept is origami electronics, which uses principles of folding and flexible substrates to create devices that can bend, twist, and even change shape without losing functionality. This approach relies on ultrathin materials such as graphene, metallic nanowires, and polymer-based nanocomposites, which maintain conductivity under mechanical deformation. Origami-inspired designs enable the integration of circuits into wearable fabrics, biomedical implants, and deployable sensors for space applications. By combining mechanical flexibility with nanoscale precision, origami electronics opens the door to foldable displays, stretchable batteries, and even self-assembling circuits that can adapt to complex environments. These innovations promise ultradense circuits, wearable electronics, and bio-integrated sensors for future healthcare and smart technologies.

As we move towards Industry Revolution 5.0, nanomaterials are playing a vital role in shaping the next generation of smart technologies. Scientists have developed advanced materials that can generate electricity simply by being bent, twisted, or squeezed. This means wearable devices such as pacemakers, motion sensors, and even smart running shoes could power themselves without batteries. The secret lies in nanoscale engineering, tiny structures that convert mechanical movement into electrical energy through effects like piezoelectricity and triboelectricity. These materials are not only nontoxic but can also be manufactured using cost-effective, scalable methods, making them practical for everyday use. Even when crumpled or folded, their conductive networks remain intact, and the material can return to its original shape without losing performance. By combining flexibility, safety, and energy harvesting, nanomaterials are paving the way for self-powered electronics that will transform healthcare, fitness, and sustainable living.

People often worry about whether nanomaterials are toxic, but this concern is usually based on a misunderstanding. Being nano-sized does not automatically make a material harmful. What really matters is the material’s chemistry, especially its surface properties and electrical charge. Nanoparticles with highly reactive or charged surfaces can interact with living cells in ways that may cause harm. However, when these materials are carefully designed to be stable and neutral, the risk of toxicity is greatly reduced. This is why medical nanomaterials, such as liposomes and gold nanoshells, undergo surface modification to make them safe and biocompatible. Scientists focus on safe design and thorough testing so that the benefits of nanotechnology, such as cleaner energy, advanced electronics, and targeted medical treatments, are not overshadowed by myths.

Malaysia is also embracing nanotechnology as part of its sustainable development strategy, particularly in clean energy. One promising innovation is the use of nanomaterials in solar cell paste. Conventional solar panels rely on silicon layers to capture sunlight, but researchers are now incorporating nanometals such as nanosilver and nano zinc oxide into the conductive paste that connects these layers. Quantum dots, tiny semiconductor crystals with tunable bandgaps, are also being explored to enhance light absorption and energy conversion efficiency. These nanomaterials improve how sunlight is captured and electricity flows, making solar panels more efficient and durable. Beyond efficiency, the integration of nanosilver and nano zinc oxide enables the development of flexible solar panels, which are lighter, bendable, and easier to install compared to traditional rigid panels. This microscopic change could have a major impact on Malaysia’s ability to harness solar power, reduce energy costs, and achieve its sustainability goals under the National Energy Transition Roadmap.

As transistor sizes are projected to shrink to just 3 to 5 nanometers by 2029, the next generation of nanoelectronics will deliver unprecedented computing power with lower energy consumption. This progress aligns with Malaysia’s Sustainable Development Goals and Shared Prosperity Vision 2030, positioning the nation as a regional leader in green technology and advanced manufacturing. Nanotechnology is no longer just about making things smaller; it is about mastering the physics and engineering of ultrathin, high-performance structures that will drive scientific discovery and practical innovation for decades to come.

By: Ts. Dr. Nurul Akmal Che Lah

Email: akmalcl@umpsa.edu.my

The writer is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Manufacturing and Mechatronics Engineering Technology, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (UMPSA).

- 44 views

Reports by:

Reports by: